Unraveling Fire: Intimate Gaze in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451

A curiosity on Ray Bradbury's use of gaze and the intimate glance in Fahrenheit 451.

Writing Skins is a reader supported author newsletter that shares excerpts from an award nominated speculative fiction writer’s craft journals. It offers a vulnerable, funny, and interesting look at the writing life, craft, and storytelling.

Craft Chat is the writing craft section of the newsletter where subscribers and me go through a subject, piece of media, or technique together.

I once dated a person who both wanted to be seen by me and also could not stand being seen, observed, looked upon, perceived in entirety no matter how false that perception was. They would ask for me to see them and then found themselves deeply uncomfortable and assaulted by the idea that there is something to see inside of them that they don’t see or can’t see or won’t allow themselves to see. An unraveling of the person we thought we were and the life we believed we’d lead.

Over the course of the eight or nine months that we were together, I watched as their life shattered from a distance.

“He wore his happiness like a mask and the girl had run off across the lawn with the mask and there was no way of going to knock on her door and ask for it back.” (Fahrenheit 451 pg. 9)

In Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury leans on an idea of the power of an intimate gaze to reverse and unravel a character and a world. You thought you were this, but really you’re this and you needed someone else to see it for you to realize it.

Fahrenheit 451 is a novel about future firemen who come to burn your books and your house and sometimes you if you are found reading or in possession of books. The main character, Guy Montag, is a fireman who starts off the story very happy (“It was a pleasure to burn.” Is the first line of the novel) until a few pages into his supposed happy existence a young girl looks at him, sees him and he’s changed in that instance: “He saw himself in her eyes, suspended in two shining drops of bright water, himself dark and tiny, in fine detail…as if her eyes were two miraculous bits of violet amber that might capture and hold him intact.” Shortly after this encounter, Montag reads a book and succumbs to delirious knowing.

What surprised me about reading Fahrenheit was that it is not a book that gets Montag to read or break from his worldly order, it is the gaze of the teen, Clarisse McClellan, that changes everything for him. Montag in fact has a book and has had a book for quite some time hidden away in his home but he’s never wanted to read it or confront his life and the world until that honest look. I think that’s what surprised me also about the person I once dated who feared being seen. The elements of their life that would soon change were already changing before I got involved with them and would be there when I was no longer in their life, but it was fine until an intimate gaze “captured and held them intact.”

Intimacy is the spark that ignites and eventually consumes Montag in Fahrenheit. He was finally seen and in that unashamed almost easy intimate gaze he can now not unsee himself and the world around him. The Montag before the shadow of a gaze is now awake and can see the world around him—not for what it is but how it is because that’s what intimacy in Bradbury stories gives us: a glimpse into how it is.

“Montage looked at these men whose faces were sunburnt by a thousand real and ten thousand imaginary fires, whose work flushed their cheeks and fevered their eyes. These men who looked steadily into their platinum igniter flames as they lit their eternally burning black pipes. They and their charcoal hair and soot-colored brows and bluish-ash-smeared cheeks where they had shaven close; but their heritage showed.”

The government gaze is the other dominating gaze of the novel. It’s the one that overshadows the novel and the more important intimate gaze shared between characters. In a way, the gaze of the government is a looming specter that exists inside the characters in order to tell them how the government wants things to be and believes they should feel. And it is this gaze by the end of the novel that is shown to be a lie during a broadcasted chase scene after Montag has murdered people and gone on the run. When the government can’t find Montag, they frame someone else and send a mechanical hound after the person and broadcast the attack saying that they have captured Montag while Montag watches his faked death on TV.

But while Montag watches the scene, Bradbury creates another intimate gaze almost as penetrating as the first that Montag experienced earlier in the novel. This gaze is shared between him and the other miscreants of society who have each memorized or bastardized major works of the Western canon that they now carry around inside their heads and those men are the only ones who truly see and know each other for who they are: the stories they tell and hold.

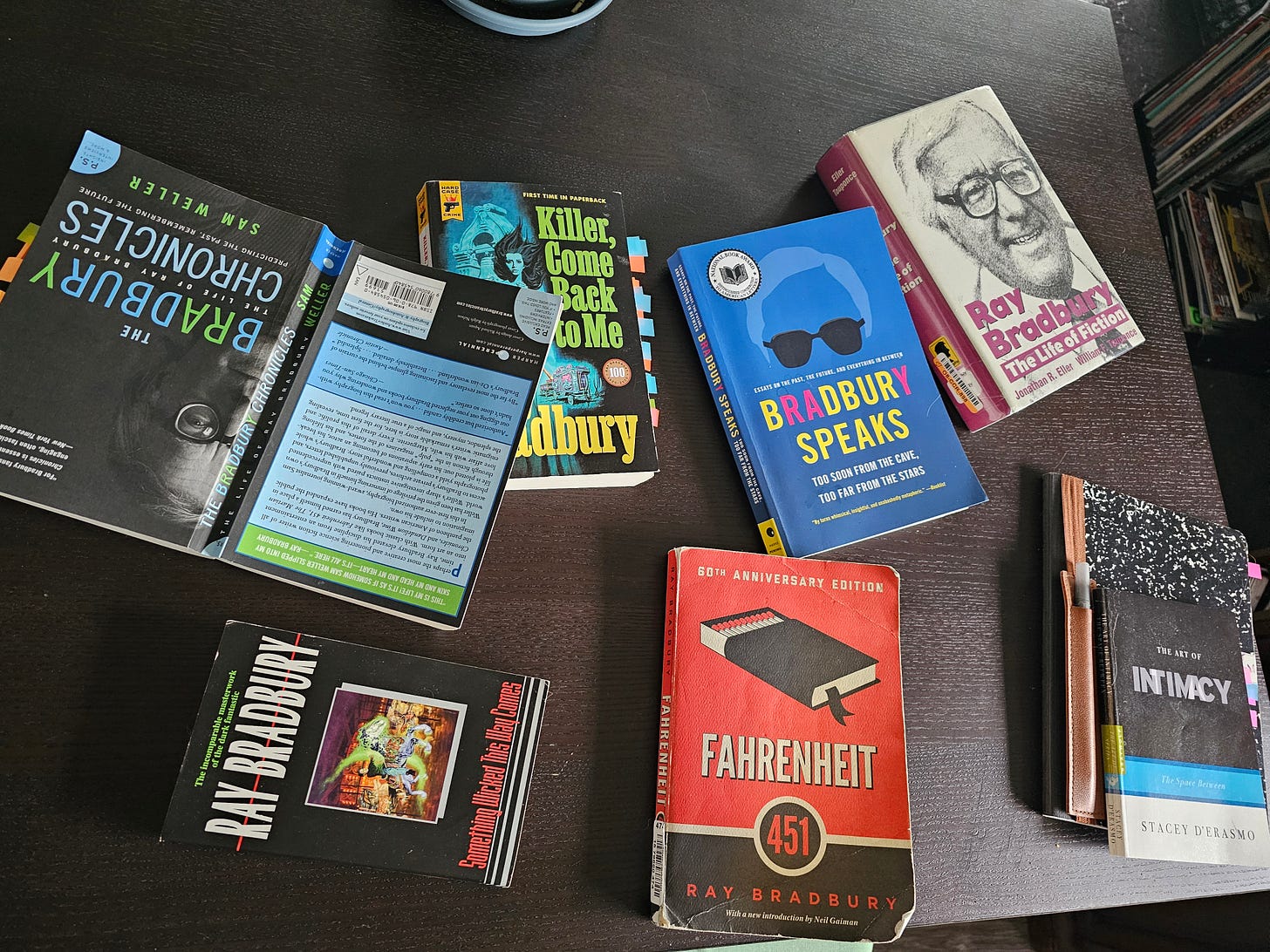

I just spent the last several months reading A LOT of Ray Bradbury and watching his interviews and lectures and thinking about his prose and life so I would love to talk to anyone about him. Do you read Bradbury? What do you think about his prose style and writing?